Are you sure you want to reset the form?

Your mail has been sent successfully

Are you sure you want to remove the alert?

Your session is about to expire! You will be signed out in

Do you wish to stay signed in?

The Graphic Novel in America

Definitions of the graphic novel vary widely, and can be based on the form, the content, or even the intent. Stephen Weiner, author of three books about graphic novels, defines them simply as “book-length comic books that are meant to be read as one story” (xi). While Weiner’s definition is primarily quantitative in nature, Roger Sabin, author of Adult Comics, sees graphic novels as qualitatively different from a comic book story arc in that they are characterized by greater complexity and thematic unity. Cartoonist Eddie Campbell declares that “graphic novel is an abstract idea. It’s a sensibility, it’s an advanced attitude toward comics” (qtd. in Deppey). To many artists, the attitude is more important than the label.

As Campbell points out in his tongue-in-cheek Graphic Novel Manifesto, a true graphic novelist “would never think of using the term graphic novel when speaking among their fellows,” but “publishers may use the term over and over until it means even less than the nothing it means already.” While publishers eagerly embrace the term as a marketing device, quite a few of the cartoonists producing the best graphic novels reject the term. Art Spiegelman’s Maus is simply referred on the back cover as “a new kind of literature.” Three of the most critically acclaimed authors of graphic novels purposely avoid using the term on their covers. Craig Thompson chose to call Blankets “an illustrated novel,” Dan Clowes’ Ice Haven is labeled a “comic-strip novel,” and Alison Bechel’s Fun Home is a “tragicomic.”

The creative and fan communities will continue to be debate about whether the term should be used at all, and, if so, how it should be applied. What is the minimum length to qualify as a novel? Which works are serious enough in intent and sophisticated enough in execution to warrant being labeled a graphic novel? Rather than being so presumptuous as to provide definitive answers to any of these questions, we simply fuel the debate by providing a chronology of works that present a complete comics story, of some length and ambition, that was either created for or collected into book form.

There has been a robust tradition of longer comics in Europe and Japan, but most of those works have not been available to an American audience until recent decades. Some of the titles listed below originated in other cultures, but the dates given usually reflect when an English translation of the book was available to an audience in the United States.

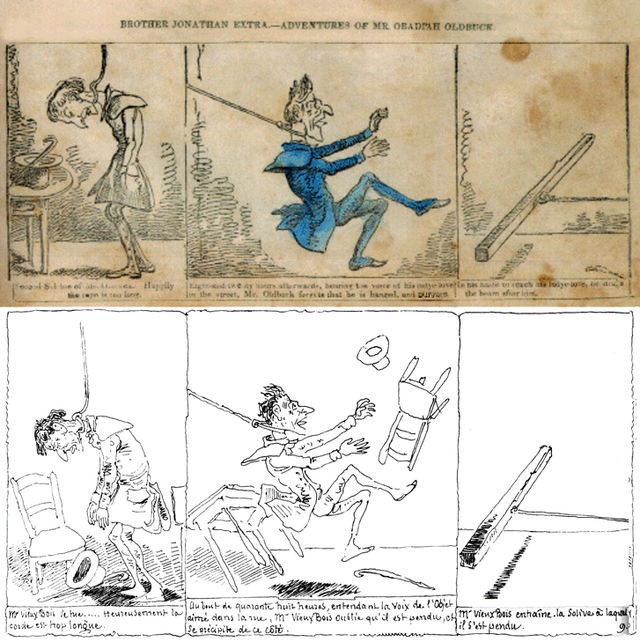

1842

The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck by Rudolph Töpffer (40 pg. / Wilson and Co.)–published in the magazine supplement, Brother Jonathan Extra no. 9, a re-formatted version of the pirated English translation of Töpffer’s 1837 work Les Amours de Monsieur Vieux Bois

1849

Journey to the Gold Diggins by Jeremiah Saddlebags by James Alexander Read and Donald F. Read (approx.. 63 pages / U. P. James)

1929

God’s Man: A Novel in Woodcuts by Lynd Ward (approx. 114 pgs. / Cape & Smith)

1930

He Done Her Wrong: The Great American Novel and Not a Word in It – No Music Too by Milt Gross (246 – 264 pgs. / Doubleday, Doran & Co.)

1931

The Four Immigrants Manga by Henry (Yoshitaka) Kiyama (112 pgs.)

1950

It Rhymes with Lust written by Drake Waller (Arnold Drake and Leslie Waller) and art by Matt Baker and Ray Osrin (128 pgs. / St. John Publications)–“Pictures Novels” across the cover (It was intended as the first in a series by St. John); “an original picture novel” on the title page

The Case of the Winking Buddha written by Manning Lee Stokes and art by Charles Raab (St. John Publications)

Mansion of Evil by Joseph Millard (Fawcett Publication / Gold Medal)

1958

Sweet Gwendoline: The Race for the Gold Cup by John Willie (144 pgs. / Nutrix)

1959

King Ottokar’s Scepter by Herge [Georges Remi] (62 pgs. / Golden Press)–one of four U.S. editions of Tintin albums Golden Press issued in 1959

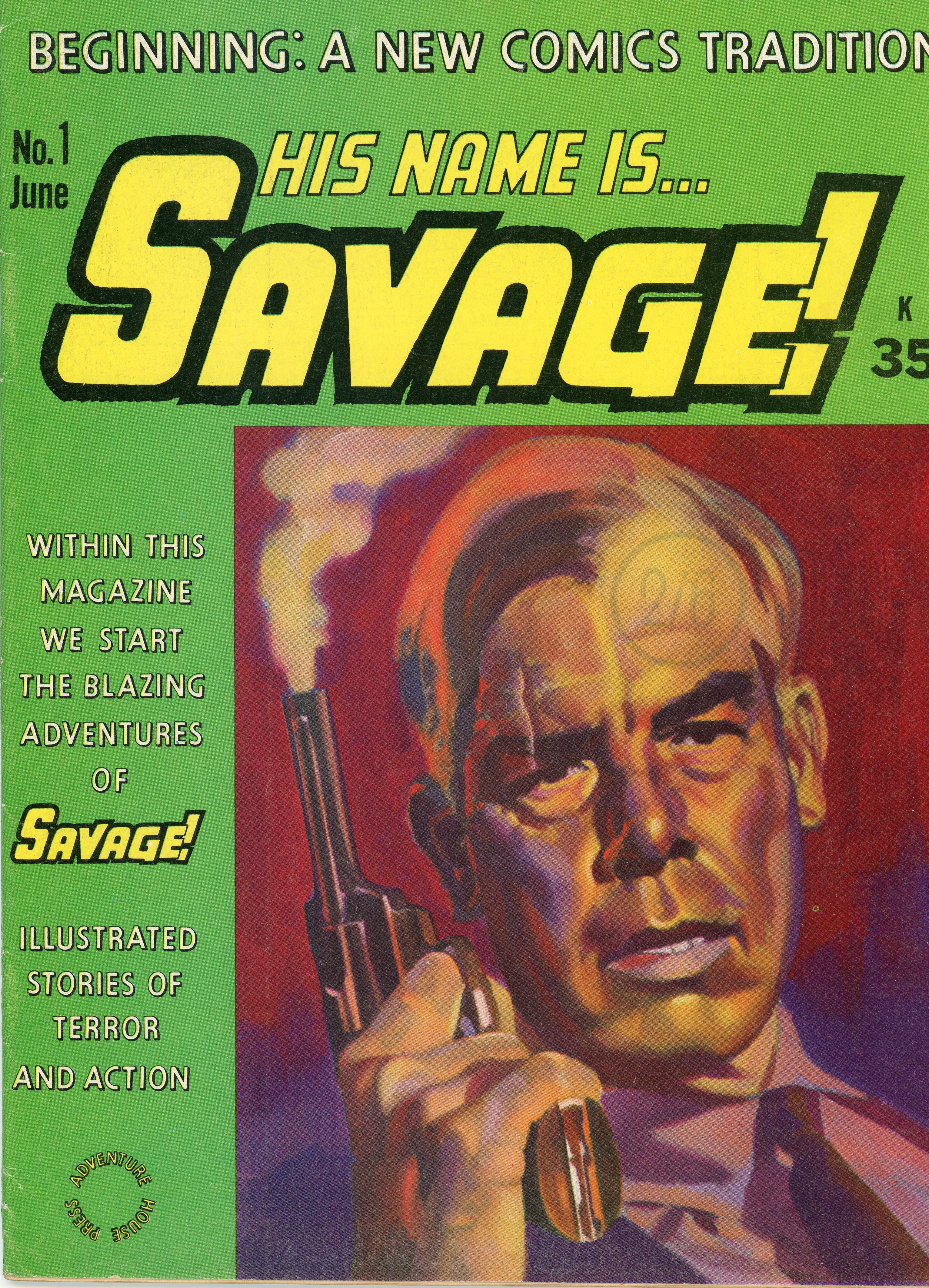

1968

His Name is . . . Savage plot and art by Gil Kane and script by Archie Goodwin (40 pgs. / Adventure House Press / magazine format)

The Adventures of Phoebe Zeit-Geist written by Michael O’Donoghue and art by Frank Springer (over 100 pgs. / Grove Press)–had been serialized in Evergreen Review from 1965 to 1966

1971

Blackmark plot and art by Gil Kane and script by Archie Goodwin (119 pgs. / Bantam Books)

1972

Tarzan of the Apes originally written by Edgar Rice Burroughs, script adapted by Robert M. Hodes, and art by Burne Horgarth (approximately 32 pgs / Watson-Guptil)

1976

Fiction Illustrated: Schlomo Raven written by Byron Preiss and art by Tom Sutton (112 pgs. / Pyramid Publications / Byron Preiss Visual Publications)–first inside page: “America’s first full-color adult graphic story revue”; back cover: “Volume one of America’s first adult graphic novel revue!”

Bloodstar by Robert E. Howard, script adapted by John Jakes and John Pocsik, and art by Richard Corben (Morning Star Press)–the front flap of the dust jacket reads: “Bloodstar is a new revolutionary concept – a graphic novel, which combines all the imagination and visual power of comic strip art with the richness of the traditional novel.”

Beyond Time and Again by George Metzger (48 pgs. / Kyle & Wheary)–a collection of the underground comic that ran from 1967-1972, one of the publishers is Richard Kyle, who coined the term “graphic novel” in the mid-60s; subtitled “graphic novel” on the title page

Fiction Illustrated: Starfawn written by Byron Preiss and art by Stephen Fabian (104 pgs. / Pyramid Publications / Byron Preiss Visual Publications )–back cover: “Volume Two of America’s first adult graphic novel revue!”

Fiction Illustrated: Red Tide by James Steranko (117 pgs. / Pyramid Publications / Byron Preiss Visual Publications)–“Visual novel” on front and back covers; “Illustrated novel” on title page; called a “graphic novel” in the introduction; actually, an illustrated novel rather than a comic

1977

Even Cazco Gets the Blues by Phil Yeh (Fragments West)

Heavy Metal Presents: Candice at Sea written by Jacques Lob and art by Georges Pichard (50 pgs. / Heavy Metal Communications)–a translation of a French graphic album, one of a dozen graphic novels Heavy Metal published from 1977 to 1979

1978

The First Kingdom by Jack Katz (Pocket Books & Simon & Schuster [soft cover])–collected the first six issues of the eventual twenty-four issue epic

Sabre: Slow Fade of an Endangered Species written by Don McGregor and art by Paul Gulacy (Eclipse Books)–“comic novel” on credits page; first graphic novel sold through the direct market

The Silver Surfer written by Stan Lee and art by Jack Kirby (Simon & Schuster / Fireside Books)

The Wizard King by Wallace Wood (64 pgs. / self-published)

A Contract with God by Will Eisner (178 pgs. / Baronet Press)–the work that popularized the term graphic novel but actually a short story collection rather than a novel; “a graphic novel” appeared on the soft cover, but not the hard cover

Empire written by Samuel R. Delany and art by Howard Chaykin (Byron Preiss)

1979

The Swords of Heaven, the Flowers of Hell concept and outline by Michael Moorcock and art by Howard Chaykin (Heavy Metal Communications)

Tantrum by Jules Feiffer (183 pgs. / Random House)–“novel in cartoons”

Comanche Moon by Jack Jackson (Jaxon) (119 pgs. / Rip Off Press / Last Gasp / Texas A&M UP)

Blackmark: The Mind Demons by Gil Kane (62 pgs. / Marvel Comics Group)–appeared in the magazine Marvel Preview # 17 and referred to as “a graphic novel” on the magazine cover

1981

Los Tejanos by Jack Jackson (Jaxon) (Fantagraphics)

Elfquest: Fire and Flight by Wendy and Richard Pini (159 pgs. / Donning / Starblaze)

1982

The Death of Captain Marvel by Jim Starlin (62 pgs. / Marvel Comics Group)–“Marvel Graphic Novel” on cover

When the Wind Blows by Raymond Briggs

The Adventures of Luther Arkwright, Book One: Rat Trap by Bryan Talbot (Never Ltd.)–first of three volumes that collected the story that had been serialized in Near Myths since 1978

Los Tejanos by Jack Jackson (Jaxon) (136 pgs. / Fantagraphics)

I Saw It by Keiji Nakazawa (52 pgs. / Educomics)–translation of the Japanese manga

1986

Maus: A Survivor’s Tale by Art Spielgelman (159 pgs. / Pantheon)

Corto Maltese: Brazilian Eagle by Hugo Pratt (Nantier, Beall, Minoustchine)–translated from the Italian

Cerebus: High Society by Dave Sim (512 pgs. / Aardvark-Vanaheim)

Batman: the Dark Knight Returns by Frank Miller (approx. 199 pgs. / Warner Books)

1987

Watchmen by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons (413 pgs. / Warner Books)

Bibliography

Deppey, Dirk. “Comic Book Culture: Eddie Campbell Interview.” excerpted from The Comics Journal #273

Sabin, Roger. Adult Comics: An Introduction. London: Routledge, 1993.

Weiner, Stephen. Faster than a Speeding Bullet: The Rise of the Graphic Novel. New York: NBM, 2003

© 2022 The Power of Comics and Graphic Novels