Are you sure you want to reset the form?

Your mail has been sent successfully

Are you sure you want to remove the alert?

Your session is about to expire! You will be signed out in

Do you wish to stay signed in?

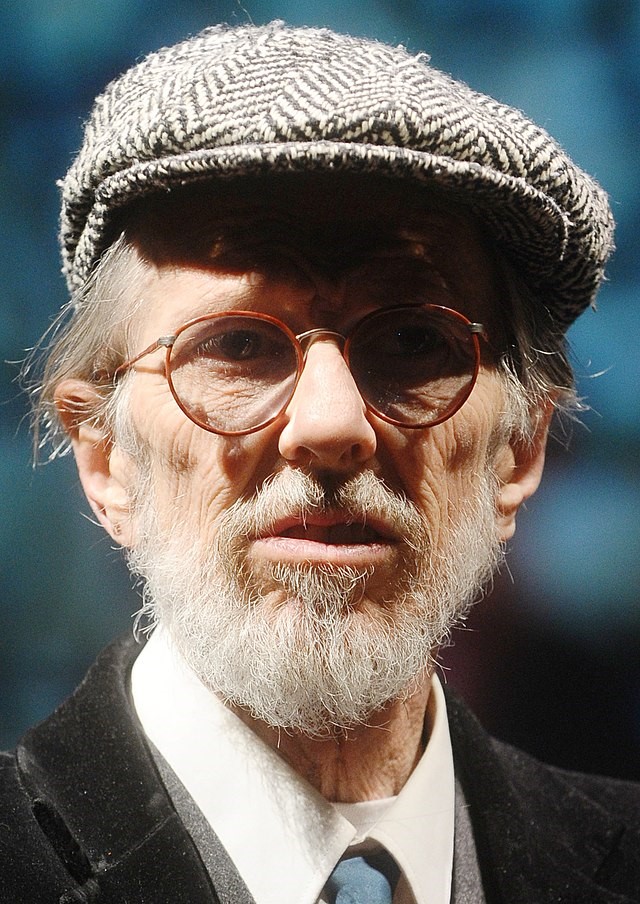

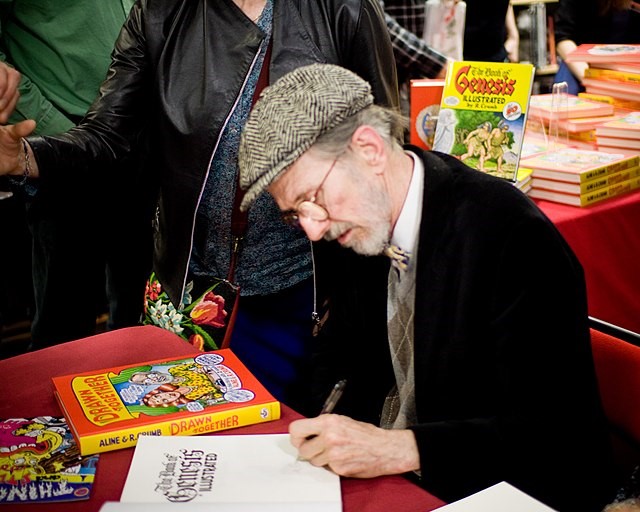

Profile: Robert Crumb

Born: August 30, 1943

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

“All my natural compulsions are perverted and twisted. Instead of going out and challenging myself against other males, all those impulses are channeled into sex.”

Select Bibliography:

1965 “Frtiz Comes on Strong” in Help! #22

1968 Zap Comix #1

1968 R. Crumb’s Head Comix

1969 Fritz the Cat movie by Ralph Bakshi

1975 Arcade: The Comics Revue

1976 American Splendor (written by Harvey Pekar)

1979 “Short History of America” in Co-Evolutionary Quarterly

1980 Heroes of the Blues cards

1981 Weirdo #1

1993 Introducing Kafka (written by David Mairowitz)

1995 Self-Loathing Comics with Aline Kominsky-Crumb

1997 The R. Crumb Coffee Table Art Book

2009 The Book of Genesis

Robert Crumb was raised by an amphetamine addicted mother and an ex-marine father that brother Charles described as “an overbearing tyrant.” Robert was painfully aware of how he disappointed his father: “All three of his sons ended up being wimpy, nerdy, weirdos. Kind of broke his heart I think.” His father refused to speak to Robert again after he saw one of the underground comix Robert had created.

Robert was a socially awkward child who turned to fantasy in lieu of friends. He enjoyed reading comic books and he loved to draw, but for young Robert Crumb drawing comic books was compulsory. He was under the thrall of his older brother Charles, “who lived mostly in the world of imagination and fantasy.” Charles organized his four siblings into The Animal Town Publishing Company, a club for discussing and producing comics. In early January 1952 Robert began drawing comics, starting with Brombo the Panda inspired by his own teddy bear, and spent “ten solid years of drawing comics with no let-up and no vacations.”

At thirteen he attempted to fit in at school.” I tried to act like I thought they were acting. It just came out all wrong and weird.” Instead he “became a shadow”; the other kids were not even aware of him. He found this freed him to be his quirky self and pursue interests such as collecting old blues albums. Yet, he was never totally at peace with his outsider status.

“Fritz was his wish-fulfillment. Fritz was bold, poised, had a way with the ladies – all attributes which Robert coveted, but felt he lacked.”

– friend Marty Phals

In his late teens he became obsessed with becoming a great artist; “that will be my revenge.” Sometimes he envisioned himself as a gallery artist, and other times he daydreamed of being a hip, successful New York commercial who would sign his work “Bob Dennis.”

In 1958 Charles and Robert produced three issues of Foo, a parody of some of their favorite horror and funny animal comics. They had little luck selling the magazine around town (the Crumbs lived in Dover, Delaware at the time), but through the letter pages of Harvey Kurtzman’s Humbug magazine they discovered a network of comics fans eager to buy Foo, or at least trade a copies of their own fanzines for it. Foo helped the Crumb brothers connect with the subculture of fanzines, and Robert developed some of his strongest teenage friendships trading and assessing comics and fanzines with pen pals such as Marty Phals.

When he turned eighteen, Crumb left home and moved to Cleveland, where he shared an apartment in Cleveland with Marty Phals. He got a job at American Greeting cards and married his first real girlfriend. Crumb was soon feeling trapped in both his job and his marriage. He began taking LSD “as a sort of substitute for committing suicide.” It did not bring Crumb freedom, but it might have contributed to his fame. Crumb had a “fuzzy” acid experience in November of 1965 and the aftereffects left him not only “crazy and helpless for six months,” but also obsessively productive. By early 1966 he filled sketchbooks with drawings of what would become his most famous characters – Mr. Natural, Devil Girl, Angelfood McSpade, Eggs Ackley, and even the keep on truckin’ guys.

“Psychedelic drugs broke me out of my social programming.It was a good thing for me, traumatic though, and I may have been permanently damaged by the whole thing, I’m not sure.”

In his late teens he became obsessed with becoming a great artist; “that will be my revenge.” Sometimes he envisioned himself as a gallery artist, and other times he daydreamed of being a hip, successful New York commercial who would sign his work “Bob Dennis.”

In 1958 Charles and Robert produced three issues of Foo, a parody of some of their favorite horror and funny animal comics. They had little luck selling the magazine around town (the Crumbs lived in Dover, Delaware at the time), but through the letter pages of Harvey Kurtzman’s Humbug magazine they discovered a network of comics fans eager to buy Foo, or at least trade a copies of their own fanzines for it. Foo helped the Crumb brothers connect with the subculture of fanzines, and Robert developed some of his strongest teenage friendships trading and assessing comics and fanzines with pen pals such as Marty Phals.

When he turned eighteen, Crumb left home and moved to Cleveland, where he shared an apartment in Cleveland with Marty Phals. He got a job at American Greeting cards and married his first real girlfriend. Crumb was soon feeling trapped in both his job and his marriage. He began taking LSD “as a sort of substitute for committing suicide.” It did not bring Crumb freedom, but it might have contributed to his fame. Crumb had a “fuzzy” acid experience in November of 1965 and the aftereffects left him not only “crazy and helpless for six months,” but also obsessively productive. By early 1966 he filled sketchbooks with drawings of what would become his most famous characters – Mr. Natural, Devil Girl, Angelfood McSpade, Eggs Ackley, and even the keep on truckin’ guys.

January 1967, with just the clothes on his back and not even leaving a note for wife Dana, Crumb “set out for the new mecca” of San Francisco with a couple of acquaintances. Crumb was drawn to the sense of total freedom that emanated from Haight-Ashbury, and he was fascinated by the hippie subculture, but he never felt comfortable around the flower children. In his long sleeve dress shirts and occasional jacket and hat, he was self-conscious about how different he looked and even imagined they suspected him of being a narc, but he was not willing to “embrace that scene.” Even though he would sometimes refer to the Haight-Ashbury crowd as “my people,” he was painfully aware of being an outsider. Crumb describes himself as a painfully shy weirdo during that period. He seldom spoke around people he had not known for a while. Second wife, Aline, says “the only voice he had was his pen.”

Crumb had gradually been finding acceptance, if not much money, for his comics work. His first comic to appear in a professional publication was a Fritz the Cat story in in a 1965 issue of Kurtzman’s Help! magazine. Getting words of praise from his idol, Harvey Kurtzman, encouraged Crumb to create material for a comic book he was going to call Fug, but the project never came to fruition. In the following years he work published in counterculture newspapers such as Yarrowstalks and the East Village Other, and in the men’s magazine Cavalier. Crumb’s fortunes rapidly improved when Apex Novelties published his Zap # 1 in February of 1968. Robert and Dana Crumb famously sold copies up and down Haight Street from a baby carriage, but publisher Don Donahue sold most of the copies through a distributor. Slowly, and reluctantly at first, head shops and record stores around San Francisco began selling Zap. Soon copies were being sold from counterculture venues across the nation.

By fall of 1968 Robert Crumb was a minor celebrity, and the acclaim from Zap lead to opportunities that made him a major celebrity. He turned down an offer to do a Rolling Stones album cover, but when Janis Joplin herself asked he did a front and back cover for Big Brother and the Holding Company’s Cheap Thrill album. Crumb was only paid $600 dollars for the work, but it became one of the most collectible album covers of all time. Years later, the original art, which was never returned to him by CBS Records, sold at auction for $21,000. Toward the end of the year Viking Press published a slightly censored sampling of his work from 1965 to 1968 in R. Crumb’s Head Comix.

Crumb demonstrated it was possible to create successful comic books independent of the mainstream industry and totally free from establishment censorship. Crumb’s growing fame fueled the growth of underground comix in general, and it was Crumb who “took the lead in breaking all existing taboos on expressions of sex, violence, and socially critical matters.”

“What I don’t want to do, what I dread more than anything, is to leave a legacy of crap.”

As Crumb’s work matured, the absurdist view of life he presented became more pessimistic and increasingly disdainful of mainstream culture. Like many underground cartoonists, Crumb lampooned the foibles and hypocrisies of middle-class America, but Crumb’s social criticism was always based in his own problems dealing with society. Being suddenly a renowned and revered counterculture hero, Crumb could be more self-indulgent about putting his sexual fantasies on the page. According to one ex-girlfriend, he masturbated to his own comics. Perhaps the more bizarre and misogynistic work was Crumb’s subconscious attempt to push people away as he became suffocated by the attention that came with celebrity. Yet, far from driving off his fans, it is Crumb’s more daring work, tapping into his unfiltered id, that has elevated his status from cartoonist to artist, seen in some quarters as the product of a tormented genius. Yet, even in the 1970s, some female cartoonists were uncomfortable with content of Crumb’s work. Through the decades, as sensibilities about representation and exploitation have changed, Crumb’s legacy is more problematic and many comics scholars are reluctant to expose students to his comics.

Crumb would probably not be pleased to be profiled in a textbook because he has never courted academic or critical attention, and believes “comics as art, with magazines of criticism and sophomoric high seriousness is nonsense.” In his teenage daydreams he saw himself producing great work that would elevate the comics medium, but after his first few LSD trips he had a different perspective. “The low, lowlife, lurid quality of comics was a very special thing, I found, and I’ve always aspired to keep it there.”

Bibliography

Barrier, Michael. “The Filming of Fritz the Cat, Part One.” excerpted from Funnyworld (Spring 1972) Funnyworld Revisited www.michaelbarrier.com

Buhle, Paul. “Political Comics.” The Education of a Comics Artist. Ed. Michael

Dooley and Steven Heller. New York: Allsworth Press, 2005: 24 – 72.

Crumb, Robert. and Peter Poplaski. The R. Crumb Handbook. London: MQ Publications, 2005.

Crumb, Robert qtd. in Juxtapoz 2.1 (1995).

Crumb, Robert. “Twenty Years Later…” R. Crumb’s Head Comix. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1988.

Zwigoff, Terry, dir. Crumb. 1994.

© 2023 The Power of Comics and Graphic Novels