Are you sure you want to reset the form?

Your mail has been sent successfully

Are you sure you want to remove the alert?

Your session is about to expire! You will be signed out in

Do you wish to stay signed in?

Linguistics: An Introduction > Student Resources > Chapter 4

The images on this page can be downloaded here, along with one additional problem for chapter 4:

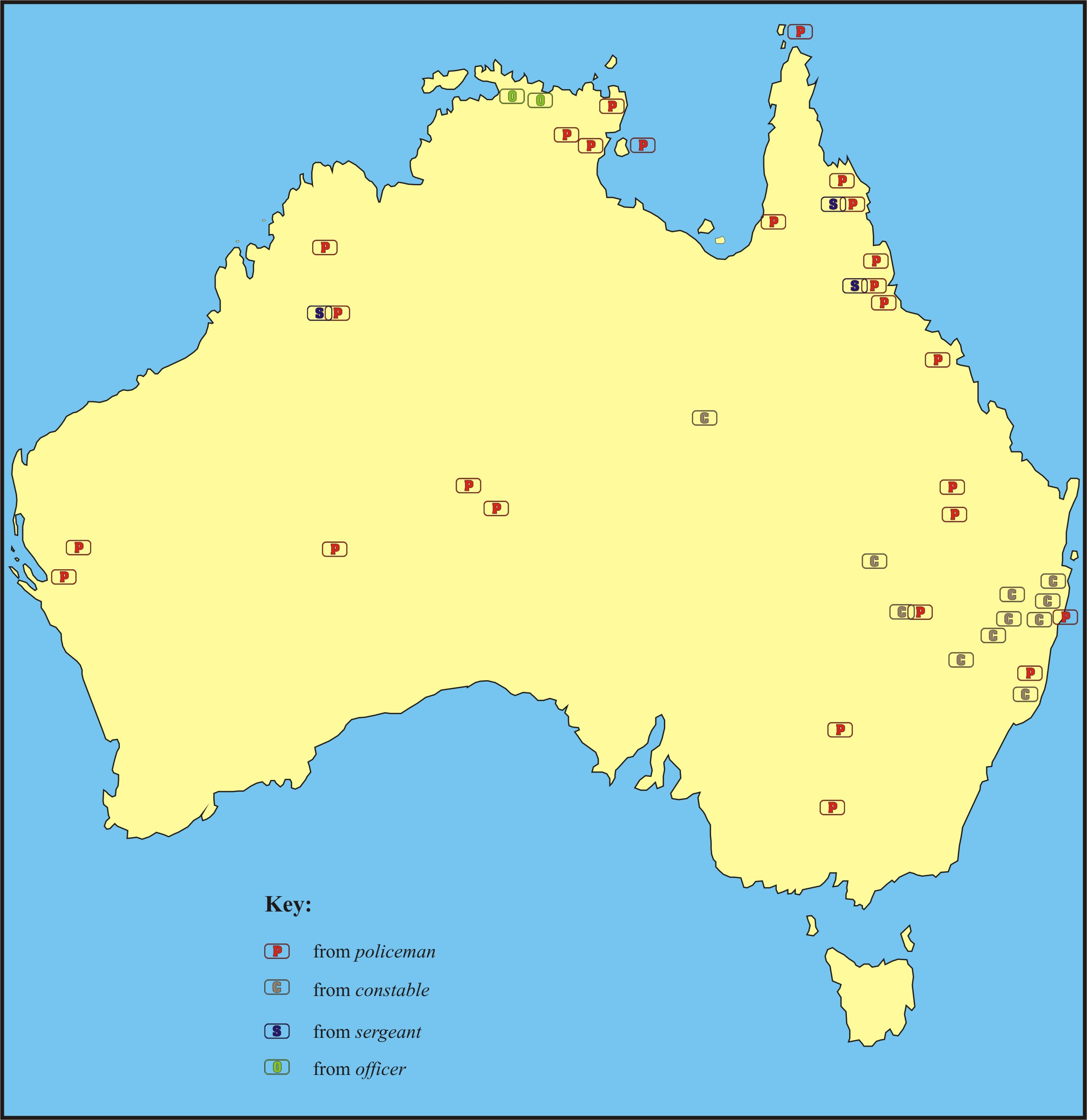

4.1 Terms for policeman in Australian languages

In the Nyulnyulan languages of Dampier Land (where Broome is located), the cognate terms linyju (Nyikina, Warrwa), linju (Yawuru), linyj (Nyulnyul, Jabirrjabirr), liinyj(a) (Bardi), and linja (Jawi) are used for ‘policeman’ — this word refers to sour, bitter, or salty tastes.

Formation

Processes of formation of words for ‘policeman’ in Australian Aboriginal languages (which lacked the concept prior to colonisaton) include almost all processes of word formation discussed in Chapter 4:

1. borrowing

2. meaning extension

3. coinage

4. derivation

5. compounding

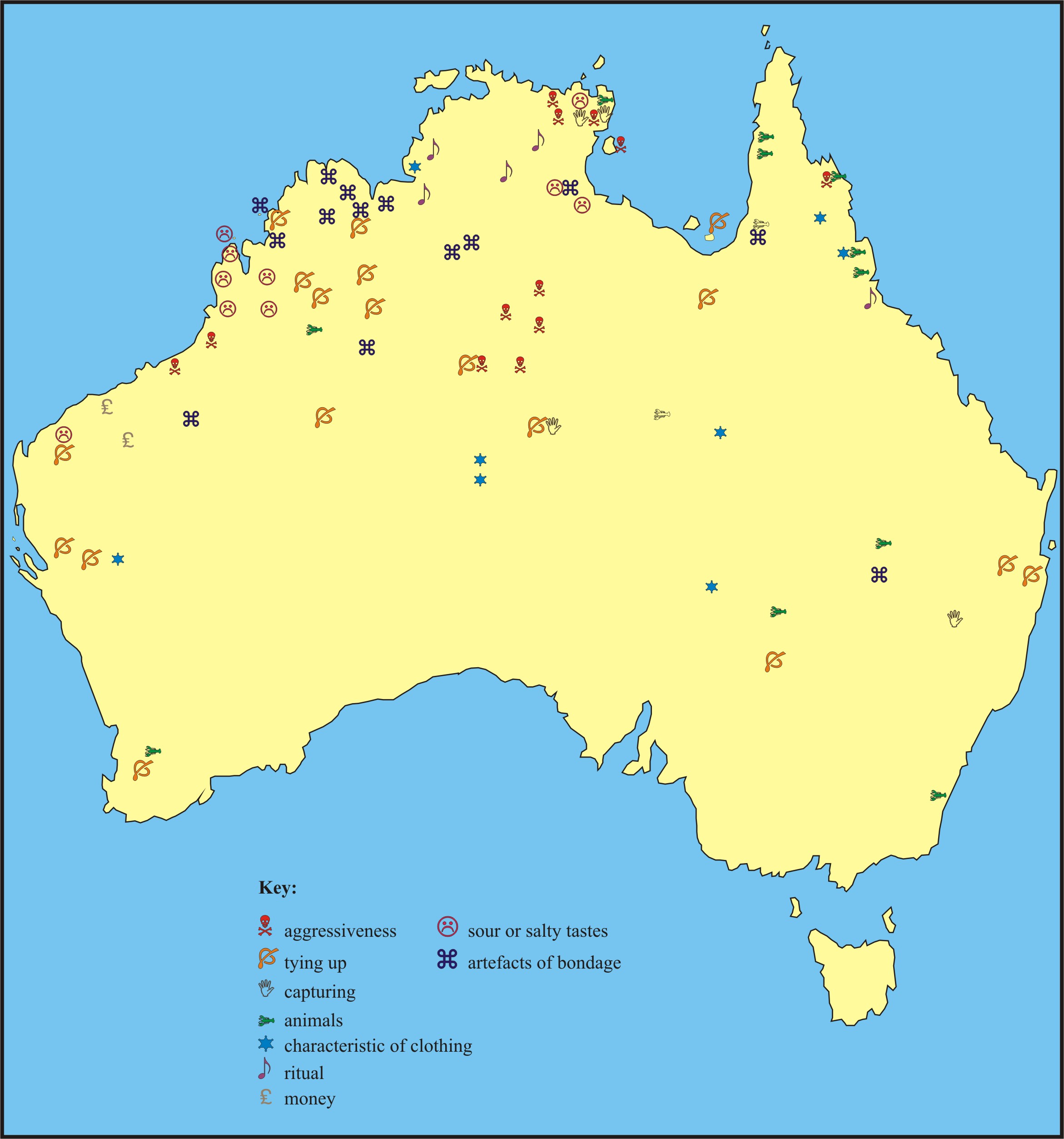

A number of recurrent meaning characteristics are identifiable.

1. Borrowing

A number of Australian languages have borrowed terms from English, most commonly the word policeman. The map shows the distributions of English borrowings, which frequently exist along side of non-borrowed terms.

2. Meaning extension

Sometimes the meaning of an existing lexical item in a language is extended to cover ‘policeman’. The most common extensions are:

• from terms for animals: for example, in Djabugay and Yidiny (Pama-Nyungan, North Queensland) one of the words for ‘policeman’ is jun.gi, which refers to a small freshwater crayfish. My favourite example is the extension of manatj (‘black cockatoo’) to ‘policeman’ in Nyungar (Pama-Nyungan, Western Australia). According to Alan Dench (pers.comm.), Nyungar people told him that the old troopers wore black (probably dark blue) uniforms with a red stripe down the side of the trousers (reminiscent of the red stripe on the black cockatoo), and rode around in packs making a lot of noise, like cockatoos.

• from terms for qualities: this is illustrated in the above-mentioned terms linyju, linju, etc. in Nyulnyulan languages. Other examples of extension include: gurndarnda ‘very salty’ in Mara (non-Pama-Nyungan, Northern Territory); kilipartta ‘angry, cheeky, on for fights (aggressive)’ in Warumungu (Pama-Nyungan, Northern Territory); and ngarniwurtu ‘hot to taste, savage’ in Martuthunira (Pama-Nyungan, Western Australia).

3. Coinage of new terms

Coinage refers to cases in which a term appears to be a pure invention, not based on any known term in the language or any other languages. Possible examples include jurrburlara in Payungu and Thalanyji (Pama-Nyungan, Western Australia), nyurdularra in Tharrgari (Pama-Nyungan, Western Australia), jarnkarra in Panyjima (Pama-Nyungan, Western Australia), and minaypura in Atampaya Uradhi (Pama-Nyungan, North Queensland). (It is of course always possible that terms such as these are not invented out of the blue, but we simply do not know what the basis for their formation is.)

4. Derivation

Many terms for ‘policeman’ involve a derivational affix attached to an existing word in the language. Thus the term in Wunambal and Unggumi (Worrorran, Kimberley) is yirrgal-ngarri (rope-with), a derived form of yirrgal ‘rope’. In some languages the term is a derived form of a verb, as in mirn-mird-gali (tie:up-tie:up-er) in Gooniyandi (Bunuban, Kimberley), mern-merd-kale-ny (tie:up-tie:up-er-masculine) in Kija (Jarrakan, Kimberley), and murd-murd-galu in (tie:up-tie:up-er) in Worlaja (Worrorran, Kimberley); literally these terms mean something like ‘tier-uper’.

5. Compounding

Compounding is another frequently used process for the formation of terms for ‘policeman’. Some examples are: wirtirr-ngumpa ‘stern-face’ in Nyangumarta (Pama-Nyungan, Western Australia), tharra malka ‘thigh stripe/mark’ in Diyari (Pama-Nyungan, South Australia), and wandu-wurril ‘hat-turned up/crossways, lopsided’ in Kuuku Yalanyji (Pama-Nyungan, North Queensland).

Main features of meaning

• aggressiveness — as a human characteristic, taste-wise (strong and/or unpleasant tastes), and aggressive/dangerous animals;

• binding — including the artefacts employed (ropes and/or chains), and the action itself;

• animal domain — in terms of some behavioural or physical characteristic of the animal reminiscent of the police (no evidence of affective evaluation);

• capturing — particularly animals that grab their prey, the action of grabbing or catching, and artefacts for capturing (rare);

• characteristic feature of clothing or adornment — particularly prominent distinguishing features such as stripes, badges, and so on;

• ritual domain — secret/sacred, taboo, wisdom, etc.; and

• money — harking back to the role of police as bankers (and “protectors of Aborigines ”) in the early part of the twentieth century.

For further information see the following article (unfortunately not available on-line):

McGregor, W. B. (2000), ‘Cockatoos, chaining-horsemen and mud-eaters: terms for ‘policeman’ in Australian Aboriginal languages’. Anthropos, 95, 3-22.