Chapter introductions

High levels of industrial competition created a stark new reality in the 1980s. Manufacturing companies in most industrial nations struggled to survive by restructuring and downsizing their activities. This signalled an economic change that continued into the 1990s and has even increased pace into the new millennium.

Despite this new challenge, most Western companies still believe operations should focus on short-term issues and leave strategy to the marketing and finance functions. However, this book argues that an operations strategy is essential for companies to compete in domestic and world markets. Without one, it will not be able to survive, let alone grow its market share.

This chapter compares the performance of nations and businesses over the past 30 years. It shows that newer ones are outperforming those with strong industrial traditions by using different operations management approaches. This has further increased the level of competition and the need to use operations as a strategic force both within businesses and between nations.

Companies invest in a wide range of functions and capabilities in order to design, make and sell products at a profit. Consequently, the degree to which a company’s functions are aligned to the needs of its markets will significantly affect its overall growth in sales and profits. Appropriate investment in processes and infrastructure in operations is fundamental to this success, whereas a lack of fit between these key investments and a company’s markets will lead to a business being well wide of the mark. If a firm could change its operations investments without incurring penalties such as long delays and large reinvestments, then the strategic decisions within operations would be of little concern or consequence. However, nothing could be further from the truth. Many executives are still unaware that what appear to be routine operations decisions frequently come to limit the corporation’s strategic options, binding it with facilities, equipment, personnel, basic controls and policies to a non-competitive posture, which may take years to turn round.1

The compelling reasons to ensure fit are tied to the invariably large and fixed nature of operations process and infrastructure investments. They are large in terms of the size of the investment (£s) and fixed in that it takes a long time to agree, sanction and implement these decisions in the first instance and even longer to agree to change them. It is similar to the oil tanker captain who, on being asked to change direction, would respond: ‘you should have asked me 20 kilometres ago.’

Having invested inappropriately, companies invariably cannot afford to put things right, both in terms of the size of the reinvestment and the time to implement the changes. The financial implications, systems development, training requirements and time to make the changes would leave the company, at best, seriously disadvantaged. To avoid this, companies need to be aware of how well operations can support the marketplace and be conscious of the investments and time dimensions involved in changing current positions into future proposals.

The last chapter introduced the concept of order-winners and qualifiers, discussed the rationale behind these perspectives and outlined their distinguishing characteristics. This chapter examines these dimensions more fully, explaining specific criteria in some detail.

The essence of strategy stems from the need for companies to gain a detailed understanding of their current and future markets. Functions are then required to develop strategies based on supporting the requirements of those markets in which the business decides it wishes to retain and/or grow share. Operations strategy (as with other functional strategies), therefore, consists of the investments, developments and actions undertaken to support the order-winners and/or qualifiers in agreed markets and for which operations is solely or jointly responsible. The pattern of decisions that results constitutes the strategy of the function.

In reality, strategies often comprise a mix of decisions, not all of which will be in line with their strategic task(s), either by default (a result of either not being conscious of the inconsistency between the decisions taken and strategic requirements, or failing to meet the need even though adequate resources and time had been provided) or by design (there will invariably be instances where companies decide not to invest adequately for pragmatic reasons). Regarding the latter, such instances do not constitute ‘poor strategy’, because ‘good strategy’ is not a result of making the right decisions but is the outcome of a company knowing what it is doing and adjusting corporate expectations in line with reality.

In summary, the key elements of functional strategy development are:

- Being party to the decisions and agreements on current and future markets

- Identifying and agreeing relevant order-winners and qualifiers whether in a market-driven or market-driving scenario

- Assessing how well these order-winners and qualifiers are currently supported

- Agreeing a pattern of decisions and actions to maintain or improve existing levels of support

- Being aware of the extent of current and future fit, any timescales involved in point 4 and adjusting corporate expectations in line with reality

- Implementing the components of strategy.

Throughout, functions need to be proactive in strategic discussions while explaining their perspectives so that the rest of the business understands them. In this way, functional perspectives form part of both the discussion and decision.

The last two chapters introduced the concepts and principles of developing an operations strategy and the key strategic task of understanding how a company competes. This chapter addresses the question of how to develop an operations strategy.

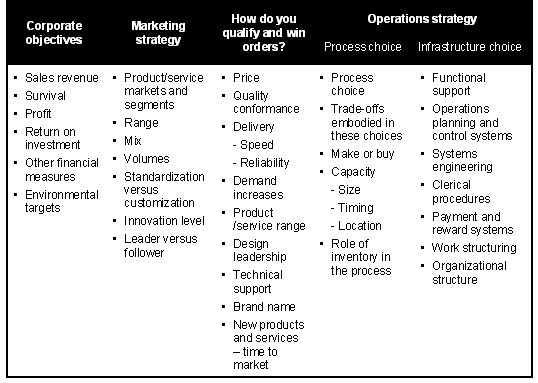

Functions manage, control and develop the resources for which they are operationally and strategically responsible. The operational tasks concern managing and controlling the day-to-day, short-term aspects of a business. The strategic tasks concern investing in and developing those capabilities to provide the qualifiers and order-winners necessary to compete in agreed current and future markets. Exhibit 4.1 shows the steps involved in analysing markets and developing an operations strategy to support them.

In addressing the key decision of which operations processes to use, many executives believe the choice should predominantly be based on the dimension of technology. As a consequence, they typically leave this decision to engineering/process specialists on the assumption that they – the custodians of technological understanding – are best able to draw the fine distinctions that need to be made. The designation of these specialists as the appropriate people to make such decisions creates a situation in which the important operations and business perspectives are at best given inadequate weight and, in many instances, omitted all together.

Operations is not an engineering- or technology-related function. It is a business-related function. Although products need to be made according to their technical specifications, they also have to be supplied in ways that win orders in the marketplace. This business dimension is the concern of operations. When making process investment decisions, therefore, companies need to satisfy both the technical and business perspectives. The former is the concern of engineering, the latter is the concern of operations.

This chapter describes the operations and business implications of process choice and highlights the importance of these issues when making investment decisions. In this way, it helps to broaden the view of operations currently held by senior executives 1 and provides a way of reviewing the operations implications of marketing decisions, hence facilitating the operations input into corporate strategy. This ensures that the necessary marketing/operations interface is made and that the strategies adopted are business rather than functionally led.

For operations, the size of process and infrastructure investments and the timescales necessary to bring about change are such that companies need to be aware of deteriorating alignment ahead of time. Chapter 5 discussed the implications of process choice, provided insights and, consequently, outlined some of the blocks on which to build operations’ strategic decisions. Assessing how well existing processes fit an organization’s current market requirements and making appropriate choices of process to meet future needs are critical operations responsibilities, owing to the high investment and timescales associated with the outcomes of these decisions.

When investing in processes and infrastructure, companies need to appreciate the business trade-offs embodied in these decisions (see Exhibit 5.16). Product profiling enables a company to test the current or anticipated level of fit between the requirements of its market(s) and the characteristics of its existing or proposed processes and infrastructure investments – the components of operations strategy (see Exhibit 2.10). The purpose of this assessment is twofold. First, it provides a way to evaluate and, where necessary, improve the fit between the way in which a company qualifies and wins orders in its markets and operations’ ability to support these criteria (that is, operations’ strategic response). Second, it helps a company move away from classic strategy building characterized by functional perspectives separately agreed, without adequate attempts to test the fit or reconcile different opinions of what is best for the business as a whole (as illustrated in Exhibits 2.4 and 2.5).

In many instances though, companies will be unable or unwilling to take the necessary steps to provide the degree of fit desired because of the level of investment, executive energy and timescales involved. However, sound strategy is not a case of having every facet correctly in place. It concerns improving the level of consciousness a company brings to bear on its corporate decisions. Living with existing mismatches or allowing the level of fit to deteriorate can be strategically sound if a company is aware of its position and makes these choices knowingly. Reality can constrain strategic decisions. In such circumstances, product profiling will help to increase corporate awareness and allow a conscious choice between alternatives. In the past, many companies have not aspired to this level of strategic alertness.

Operations is a complex function and managing this complexity is a key strategic task. Complexity does not come from the nature of the individual tasks of the job, but rather the number of aspects and issues involved, the interrelated nature of these and the level of fit between the strategic task and the operations process and infrastructure capability. In all but highly technical, special product market segments, it is not difficult to cope with the technology of the product or process. In most situations, the process technology involved has been purchased from outside, with appropriate engineering and technical support provided for operations. In a similar way, product design and the associated technology is provided by the customer and/or the design function. As such, neither process nor product technologies are generally difficult for operations to understand or manage.

The complexity in operations results from the size of the management and strategic task it faces. The management task comes from the number and interrelated nature of the tasks and issues involved. 1 The strategic task reflects the level of the fit between the strategic objectives and the operations process and infrastructure capability. Focus is one approach to organizing operations so the size of its management and strategic task is reduced.

The principles and concepts underpinning focus were outlined in the last chapter. We now turn our attention to the steps to take when focusing operations.

The markets that businesses compete in have different needs to each other. Operations must therefore cope with the differing requirements placed on them. Increasingly, operations is using focused facilities or plant-within-a-plant configurations to meet these varying demands. However, before discussing the steps to achieve focus, we should consider the origins of existing facilities, how they are arranged and the reasons for these decisions.

Companies rarely, if ever, own the resources, facilities and activities necessary to make a product from start to finish including delivery to customers. The decision on what to make in-house and what to buy and the task of managing the supply chain that results are key strategic issues within a company and ones that fall within the remit of operations. They concern the width of the internal phase of the supply chain (how much of a product is made in-house), the degree and direction of vertical integration alternatives and the links and relationships at either end of the spectrum with suppliers, distributors and customers (the external phase of the supply chain).

Both the make-or-buy decision and the task of managing the supply chain have major ramifications for a business. They impact growth and level of success and are crucial to survival. The corporate stance and response on both these key issues need to be the result of business-based discussions set in appropriate strategic context and involving sufficient recognition of the integrated nature of the resources and capabilities that forge a company’s ability to compete.

What a company decides to make or buy will impact its potential to be successful in its current markets, while restricting or facilitating its ability to change direction in the future. Having made the decision, a company needs to appreciate that the various elements involved will invariably impact many of the order-winners and qualifiers in its own markets. Traditional corporate approaches, however, typically fail to recognize the integrated nature of the whole and the need to proactively manage all elements in line with its own market needs. Developing cooperation and improving coordination are not just good things to do but are essential if a company is to compete successfully now and in the future. In the past, the activities comprising the supply of materials through to the distribution of products to customers, although financially significant, were considered strategically peripheral. Now companies are recognizing that the ownership of activities and capabilities is not what matters but rather the ability to manage these in support of their markets.

Once companies identify the processes to best support market order-winners and qualifiers, they must choose the appropriate infrastructure to manage these processes. As illustrated in Exhibit 10.1, businesses must develop processes and infrastructure that are aligned with market order-winners and qualifiers. Infrastructure developments involve high investment levels that are difficult to change and set operations performance parameters. Thus the need to align infrastructure to markets is as critical as processes and, for some companies, more so.

Notes

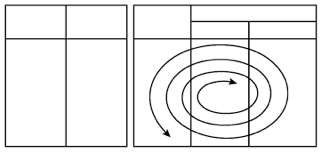

- Although the steps to be followed are given as finite points in a stated procedure, in reality the process will involve statement and restatement, for several of these aspects will impinge on each other.

- Column 3 concerns identifying both the relevant order-winners and qualifiers.

- Press enter to add another item

Exhibit 10.1 Framework for reflecting operations strategy issues in corporate decisions

Markets are dynamic and constantly changing. Businesses must identify these changes and develop capabilities to support them (see Exhibit 10.2).1 While the overall infrastructure investment is similar to that made in processes, it can be broken down into smaller elements, such as functional support, operations planning and control systems, quality assurance and control, systems engineering, clerical procedures, payment and reward systems, work structuring and organizational structure. Taken individually, each element is often easier and cheaper to modify than the processes used to deliver products and services. For this reason, businesses tend to meet market changes by modifying and realigning infrastructure. Only if market needs cannot be met through infrastructure developments will subsequent process investments be made.

Exhibit 10.2 Strategic awareness ensures businesses identify market changes and develop the capability to support them

The purpose of this chapter is to provide some critical observations on two fundamental aspects of managing businesses: the accounting and finance function’s contribution in terms of data provision, processes, controls and insights; and the measures of performance used by companies. The observations reflect an operations executive’s perspective and hence they may be seen as provocative when examined by others in an organization. If this causes debate between operations and the rest of the business, the purpose of the chapter has been well served.

With operations invariably tasked with meeting many of the financial targets and performance measures within organizations (and understandably so as it accounts for so much of the costs and investments), it is essential that the premise on which these targets and measures are built and the data used to calculate them are sound. Where this is not so, the extent of the potential inaccuracy (both data processes and insights) remains unexposed and is then built into corporate expectations. Being unaware, companies set aside these inherent deficiencies, base targets and measures on available data and consequently fail to evaluate performance on reality.