Image Bank

Below you’ll find images to accompany your reading of American Drama, including posters from plays, images of theatres and rehearsals, and portraits of playwrights.

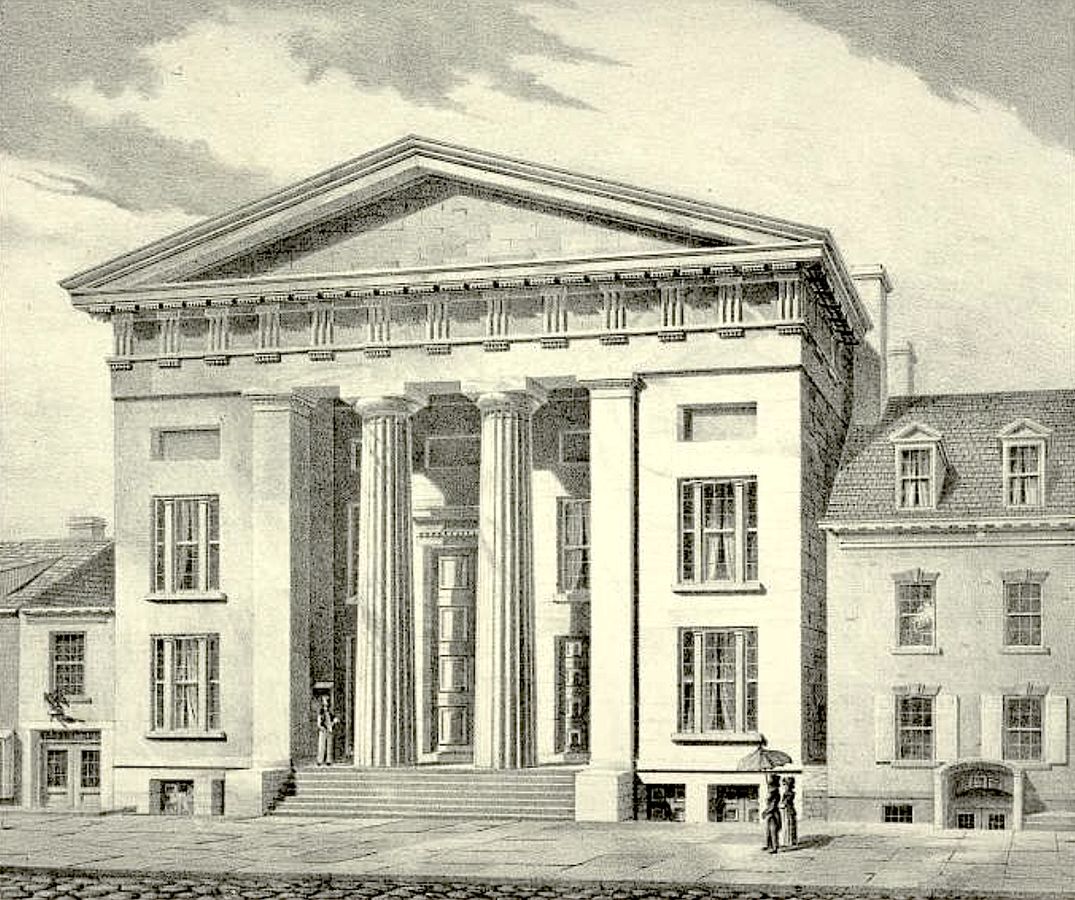

The Bowery Theater (The New York Theater), 1826.

Never officially named “the Bowery Theater,” this edifice was referred to as such throughout most of the 100 years of its existence. It was established by a group of wealthy residents of its Lower East Side environs, who wanted an elegant entertainment venue close to home and who hoped that the impressive structure with its intelligent theatrical fare would boost the moral and intellectual climate most often associated with the Bowery. For better or worse, the “b’hoys” who ran the streets of this neighborhood soon predominated in the audience and influenced the entertainment presented; the Bowery Boys were in fact a gang whose headquarters were right next door, perhaps inviting the several fires (from rival gangs) that destroyed the theater itself five times between 1826 and 1929.

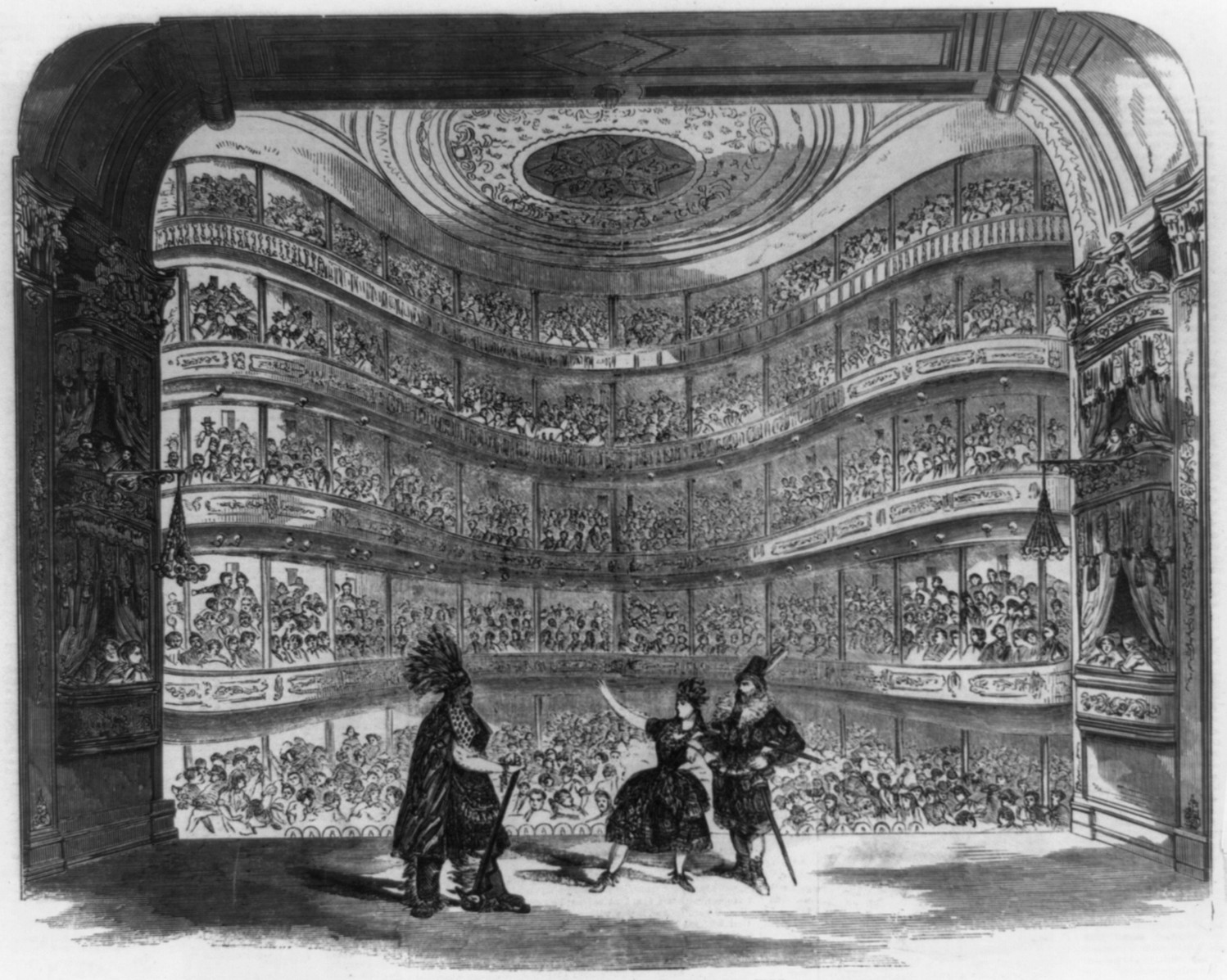

Bowery Theater (interior), 1856.

This remarkable engraving (artist unknown) from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated provides an excellent sense of the scale of early American theaters; initial iterations of the Bowery sat 3500, while later renovations increased seating to 4000. Once this theater became a venue for the lower-class denizens of the surrounding neighborhood, the great (and great-winded) Edwin Forrest was a regular attraction; from the actors depicted in the foreground here, it is possible that the scene is from Forrest’s enthusiastically received Metamora: Or, the Last of the Wampanoags (1829).

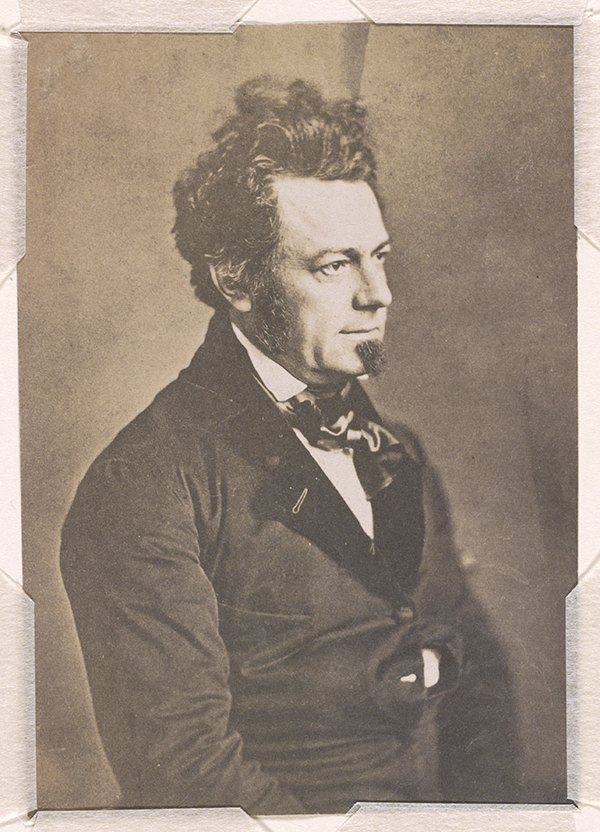

Edwin Forrest (1806-1872)

Forrest was the biggest star of the early American stage, beloved by working-class, Jacksonian-era audiences for his vigorous acting style and booming voice. He is credited with encouraging drama on American themes through his an annual playwriting contests; his most famed roles (which he repeated hundreds of times during his career) were Metamora, Jack Cade, and Spartacus (in The Gladiator [1836]). Forrest is infamous for instigating the Astor Place Riot of 1849, in which dozens were killed and hundreds injured.

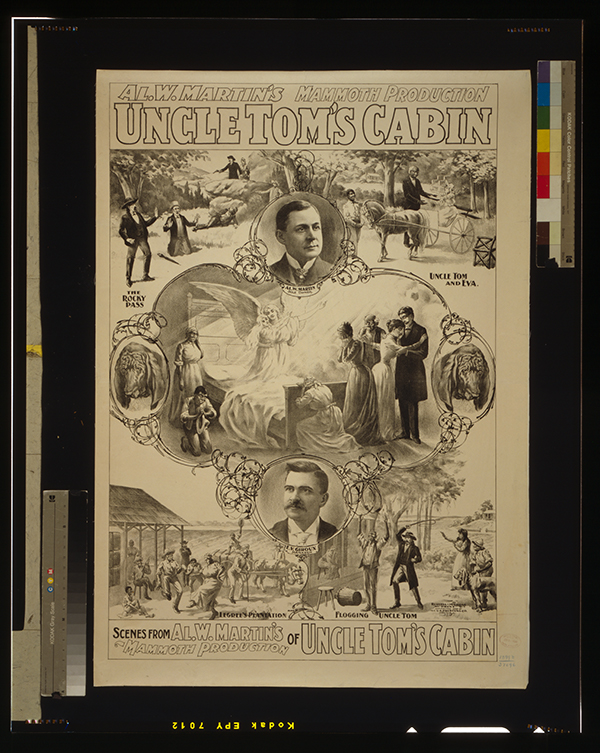

Al. W. Martin’s Mammoth Production, Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1899)

This advertisement announced the arrival of a traveling “Tom show” at the end of the nineteenth century, when dozens of touring companies crisscrossed the country, bringing this beloved American entertainment to the poorly schooled hinterlands. In these remote locales, an annual staging by the Tommers was as eagerly anticipated as its lowbrow cousins, the tent revival, the Wild West show, and the circus. This show’s “mammoth” aspect is indicated by illustrations of detailed scenery, large-scale slave song-and-dance routines, and live animals (e.g., the bloodhounds that chase Eliza across the frozen Ohio River), pictured on the right and left margins.

Minstrel Performers, c. 1855

This still shot is notable not only for its white actors in blackface but its use of blackface drag for added comic effect. In addition, the characters are dressed like plantation owners instead of in humble slavery garb, adding the masquerade of social class and the satiric intent of mocking the presumed tendency of low-born blacks to put on airs.

Big Minstrel Festival, c. 1898

Yet another mammoth-style touring production with numerous white actors in blackface (and half in blackface drag), executing elaborate choreographies in fancy dress. The many investors’ names before the title may remind readers of another oversized American production from the early twentieth century, Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus, as well as suggest the manner in which show owners pooled resources to develop these large attractions.

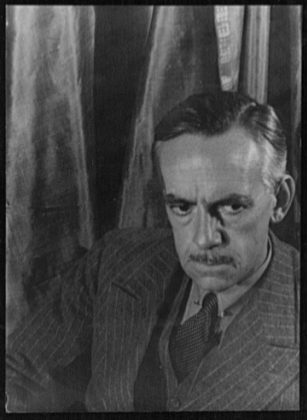

Eugene O’Neill (1888-1953) by Carl Van Vechten, 1933

Carl Van Vechten was a famed patron and photographer of literary, theater, and film figures in the first half of the twentieth century. This brooding portrait was taken after O’Neill’s most successful plays had been produced, but before the masterpieces from later in his career – presented in the years after O’Neill’s death – had reached an audience.

Elmer Rice (1892-1964) by Carl Van Vechten, 1934

When this portrait was taken, Rice had already enjoyed success with his expressionist masterwork The Adding Machine (1923) and his Pulitzer Prize-winning Street Scene (1929).

Clifford Odets (1906-1963) by Carl Van Vechten, 1935

When this portrait was taken, Odets was having his stellar year with the Group Theater, when Waiting for Lefty and Awake and Sing! were both produced.

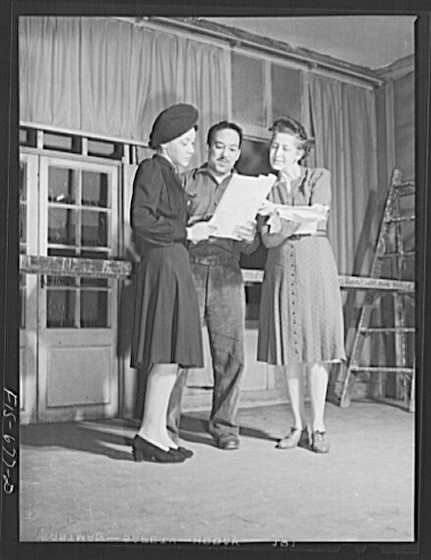

Rehearsing a Langston Hughes play, 1942

Hughes is pictured in the center of this photo by Farm Security Administration photographer Jack Delano at the Good Shepard Community Center in Chicago, Illinois.

Marlon Brando (1924-2004) by Carl Van Vechten, 1948

Carl Van Vechten was a famed patron and photographer of literary, theater, and film figures in the first half of the twentieth century. Marlon Brando was hugely successful in this well-received play by Tennessee Williams and starred in the 1951 film of the same name.

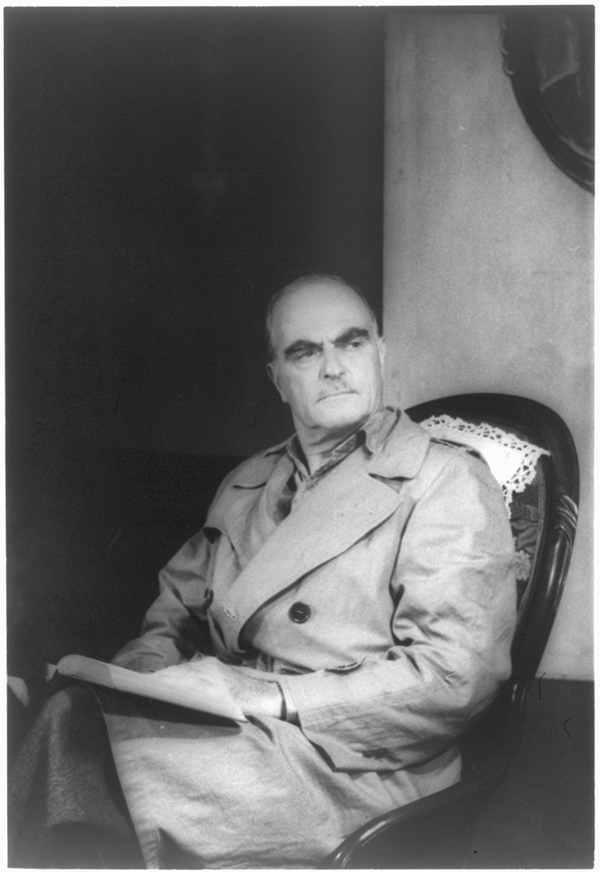

Thornton Wilder (1897-1975) by Carl Van Vechten, 1948

Wilder was photographed here in the lead role of Mr. Antrobus from his own award-winning play, The Skin of Our Teeth.

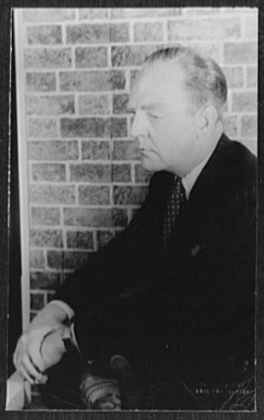

William Inge (1913-1973) by Carl Van Vechten, 1954

Carl Van Vechten was a famed patron and photographer of literary, theater, and film figures in the first half of the twentieth century. This portrait of Inge was taken following production of Bus Stop (1953), the second of his four hugely successful plays in the 1950s.