Are you sure you want to reset the form?

Your mail has been sent successfully

Are you sure you want to remove the alert?

Your session is about to expire! You will be signed out in

Do you wish to stay signed in?

The Indian Mutiny of 1857

Study the Sources A to E and then answer the questions that follow.

Source A:

| An article in The Times, 8 June 1857. To bring high-caste Hindoos into contact with lard is, of course, a mistake, but we doubt if it would in itself lead to disloyalty extending over several months. Those who know India well are not unprepared for the appearance of a restless, sullen, disorderly feeling on the part of the millions whom we rule, and especially of the troops...By education, by a glimpse of history and natural science, by the spectacle of railways and telegraphs, and by the great events which have lately passed in Europe, the Hindoo had been roused from his sluggishness. In the old times when the sepoys had no knowledge and no ambition, there was pretty nearly always something for them to do. An enemy was always on our frontier, and there were tribes of robbers, murderers or fanatics to be put down. But now we have conquered all enemies within and without. There is no activity, no excitement beyond monotonous routine duties. We cannot help feeling that this dull and aimless existence is too much even for the apathy of the Hindoos. We can well imagine the effect on the quick, suspicious temper of a Hindoo of all that is passing in India. Everything around him is in a state of change. But the sepoy has time to brood over imaginary wrongs and to suspect that he is subjected to cunning temptations. It may be that this ill-feeling is the last stand made by the Hindoo mind against the growing influence of European culture. It is not impossible that at a time when widows are marrying and men of all castes are sitting together in a railway carriage, the last efforts of those utterly resistant to change should be made. Source: The Times, 8 June 1857. |

Source B:

| A soldier’s account of the relief of Cawnpore When we reached the Bibigarh and saw the horror inside, none of us could speak. It looked as though cattle had been slaughtered in there. The walls were covered with bloody handprints and on the floor were pieces of human limbs, clothing, bibles, shoes, trinkets and lockets...Looking into a well, I saw that the severed heads, limbs and mangled bodies had been thrown into it and it was full to within six feet of the top. I have faced death in every form, but I could not look down that well again. Source: Quoted in J. Harris, The Indian Mutiny, Hart-Davis MacGibbon, 1973. |

Source C:

| Letter from Lord Canning, Governor-General of India, written shortly before the end of the Mutiny. One of the greatest difficulties which lie ahead will be the very violent bitterness of a very large proportion of the English community against every native Indian of every class. There is a raging and indiscriminate vindictiveness, even amongst many who ought to set a better example, which it is impossible to contemplate without something like a feeling of shame for one's fellow-countrymen. Not one man in ten seems to think that the hanging or shooting of forty or fifty thousand mutineers can be anything else but right; nor does it occur to them that it is simply impossible for the Sovereign of England to hold and govern India without employing and trusting natives. There are some who entirely refuse to believe in the faithfulness or goodwill of any native towards any Europeans. Source: Quoted in A. C. Benson and Viscount Esher, The Letters of Queen Victoria, John Murray, 1907. |

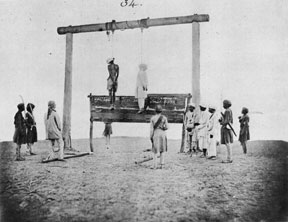

Source D: The hanging of mutineers after the Indian Mutiny, 1857

Source: The British Library

Source E: Contemporary drawing of mutineers about to be blasted from cannons

Source: Mansell Collection, Katz Pictures Ltd